Hi everyone!

This intent of this blog is to provide inquirying educators with the knowledge they need to be able to carry out action research in their classrooms. Teacher development through action research is a primary interest of mine and it is an approach that I hope to engage with the primary and elementary science teachers on my staff for the upcoming school year. As part of my Master of Education at Memorial University, I have developed a comprehensive collection of resources pertaining to teacher action research and, as such, have become quite knowledgable in this area. In addition, my research assistant position with Dr. Karen Goodnough at the faculty of education has allowed me to gain immense experience in the faciliatation of such research as I assisted in the implementation of the teacher action research project, Science Across the Curriculum. Combined, these lived experiences have provided me with significant insights regarding teacher research with respect to benefits, challenges, required supports, teacher perceptions, and impacts on the processes of teaching, learning and educational decision making. I hope that the information on this site is beneficial to you and I would invite you to share you thoughts on action research as well as your experiences with this sort of professional development.

What is Action Research?

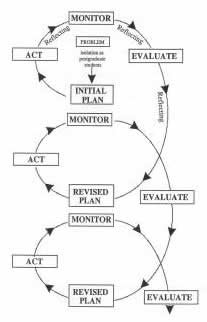

According to Hendricks (2006), “democratic workplaces produce employees that take ownership of their work, which increases both morale and productivity” (p. 6). It was with this vision in mind that social psychologist Kurt Lewin (1946) first proposed the phenomenon of action research; a research methodology where practitioners directly engage in the systematic inquiry of self-identified issues. Known as the father of ‘action research and planned change’ (Schein, as cited in Burnes, 2004, p. 978), Lewin (1946) referred to the process as one where knowledge gained from one inquiry becomes the impetus for additional inquiry; “a spiral of steps, each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action, and fact-finding about the result of the action” (p. 209).

Building on Lewin’s vision, Stenhouse (1975) later lead the ‘teacher as researcher’ movement in the United Kingdom; adopting and promoting teacher action research as he encouraged educators to enhance their practice by conducting research in their own classrooms. Others have described action research as the investigation of “a problem or area of interest specific to a professional context” (Alberta Teachers Association, 2000, p. 2), “systematic, intentional inquiry” (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1993, p. 5), “disciplined inquiry…to improve the quality of an organization” (Calhoun, 1994, p. 7), “researching your own learning” (McNiff, 2002, p. 15), and a process where “research leads to action and action leads to evaluation and further research” (Burnes, 2004, p. 984). Currently, teachers worldwide are participating in a number of action research initiatives within various educational contexts; collaborating with their peers to investigate issues directly related to their classrooms and their students as they aspire to improve their practice and effect sustainable change. (Cochran Smith & Lytle, 1999; Feldman, Rearick, & Weiss, 2001; Peters, 2004; Heindricks, 2006; Sagor, 2000).

Building on Lewin’s vision, Stenhouse (1975) later lead the ‘teacher as researcher’ movement in the United Kingdom; adopting and promoting teacher action research as he encouraged educators to enhance their practice by conducting research in their own classrooms. Others have described action research as the investigation of “a problem or area of interest specific to a professional context” (Alberta Teachers Association, 2000, p. 2), “systematic, intentional inquiry” (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1993, p. 5), “disciplined inquiry…to improve the quality of an organization” (Calhoun, 1994, p. 7), “researching your own learning” (McNiff, 2002, p. 15), and a process where “research leads to action and action leads to evaluation and further research” (Burnes, 2004, p. 984). Currently, teachers worldwide are participating in a number of action research initiatives within various educational contexts; collaborating with their peers to investigate issues directly related to their classrooms and their students as they aspire to improve their practice and effect sustainable change. (Cochran Smith & Lytle, 1999; Feldman, Rearick, & Weiss, 2001; Peters, 2004; Heindricks, 2006; Sagor, 2000).

Why is it Important?

It has been suggested that unilateral decisions regarding educational change have led to a period of disillusionment in the teaching profession as teachers become exceedingly frustrated with the myriad of educational reforms imposed from above (Dibbon, 2004; Fullan, 2001; Goodson, Moore, & Hargreaves, 2006; Knight, 2000; Marantz Cohen, 2002; Younghusband, 2005; Zimmerman, 2006). Furthermore, feelings of dissatisfaction, lack of control in their profession and under appreciation of their expertise is leaving many teachers in a state of low self-efficacy and low self-esteem (Goodson, Moore, & Hargreaves, 2006; Neito, 2003; Younghusband, 2005).

Upon exploring numerous studies examining the impact of classroom based inquiry on the self-efficacy, autonomy and empowerment of teacher researchers, it becomes apparent that teacher action research is a viable option for providing meaningful professional development opportunities for educators. Moreover, with adequate support from administrators, colleagues, and experienced facilitators, teacher researchers can become empowered within their profession and make significant contributions to school improvement and educational change initiatives.

Benefits of Action Research

- Allows teachers to realize their potential as change agents (Fullan, 2001; Heindricks, 2006; Sagor, 2000)

- Promtes autonomy, self-efficacy, and teacher confidence (Crow, Adams, Bachman, Petersen, Vickrey, & Barnhardt, 1998; Farrell, 2003; Henson, 2001)

- Empowers teachers to begin to advocate for institutional and curricular changes (Fry, Fugerer, Harvey, McKay, & Robinson, 1999; Warrican, 2006)

- Facilitates the development of a strong pedagogical content knowledge with respect to curriculum outcomes, instructional methodologies, and assessment techniques (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1999; Goodnough, 2005)

- Promotes critical reflection and self-inquiry into best teaching practices (Crow, Adams, Bachman, Peterson, Vickery, & Barnhardt, 1998

- Allows educators to be the creator of their own knowledge (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1999; Heindricks, 2006)

- Validates teacher expertise and knowledge of teaching and learning (Farrell, 2003; Feldman, Rearick, & Weiss, 2001; Fullan, 2001; Heindricks, 2006, Sagor, 2000; Sardo-Brown, 1995)

Action Research as Empowering Professional Development

According to Short (1994), the empowerment of teachers can be described in terms of six specific dimensions; a) decision making, b) professional growth, c) status and respect, d) self-efficacy, e) autonomy, and f) impact on school life. Intrinsically related, these six elements serve to engender a teaching environment that promotes collaborative decision making, validates teacher expertise, and recognizes the importance of meaningful professional development. Furthermore, teacher empowerment has been linked to increased job satisfaction (Rinehart & Short, 1994; Wu & Short, 1996), enhanced school improvement initiatives (Romance & Vitale, 1993), and organizational commitment (Bogler & Somech, 2004; Wu & Short, 1996).

The potential of action research as empowering professional development has been evident in the teacher education literature for a number of years. Numerous empirical studies have examined teacher-lead inquiry in a number of educational contexts. Furthermore, many of such studies have identified action research’s empowering capability as an evident and important theme within their findings. Such studies consistently contribute to the mounting evidence supporting teacher inquiry and action research as a means to both validate the professional knowledge of teachers and empower teachers within their profession.

The potential of action research as empowering professional development has been evident in the teacher education literature for a number of years. Numerous empirical studies have examined teacher-lead inquiry in a number of educational contexts. Furthermore, many of such studies have identified action research’s empowering capability as an evident and important theme within their findings. Such studies consistently contribute to the mounting evidence supporting teacher inquiry and action research as a means to both validate the professional knowledge of teachers and empower teachers within their profession.

Evidence of the Empowering Capacity of Action Research

- Henson (2001) - At the conclusion of their action research project, almost half of the participants in this study listed empowerment as a benefit of their involvement. They defined empowerment as “gaining new information that allowed them to try new things in their classroom” (p. 828).

- Farrell (2003) - In this study, increased self-efficacy emerged as a common theme; with participants perceiving both increases in their ability to influence decision making as well as exuding a heightened self-awareness within their reflections on practice. With respect to empowerment specifically, one participant stated, “I was powerful. I was able to see how it (action research) made a difference and how I could move out and make a difference” (p. 17). Moreover, they exhibited a stronger belief in their ability to motivate students; demonstrating significant gains in both self-confidence and autonomy.

- Crow, Adams, Bachman, Peterson, Vickery, & Barnhardt (1998) - According to the authors, the teachers in this project often expressed a renewed enthusiasm for their teaching and were excited about their new role as “informed change agents in their classrooms” (p. 16). This was often associated with a feeling that they could make a difference in their classrooms and in their schools.

- Viechnicki, Yanity, and Olinski (1997) - Reported on multiple strands of a teacher/intern action research project that had been on-going for two years. The authors remarked that action research encouraged professionalism and allowed both the in-service and pre-service teachers to engage in meaningful research borne out of their own needs and the needs of their students. They concluded that “for these individuals, action research serves as a tool for empowerment. Many had never participated in research, so the sense of accomplishment and pride that was exhibited was a beautiful thing to see” (p. 12).

- Capobiance, Lincoln, Canual-Browne, and Trimarchi (2006) - Participants in a self-study on the use of action research, the authors rereported experiencing growth in several areas such as instructional approaches, authentic assessment, and impacting on student attitudes towards science. In addition, they reflected on the increases in self-efficacy and self-confidence they experienced as a result of their involvement. They referred to their experience with teacher action research as “one of the most productive and powerful experiences in their teaching career” (p. 76).

- Feldman, Rearick, & Weiss (2001) - The authors concluded that, for teachers in their AR program, changes in the self-confidence and the perceived impact of their new orientations towards teaching and learning made it more likely that these teachers would act as empowered “levers of change” (p. 19) within their respective educational settings

- Teachers in the aforementioned studies generally displayed ownership over self-proposed initiatives (Warrican, 2006) and exuded increased confidence in both their teaching abilities and their ability to motivate students and impact learning (Farrell, 2003; Feldman, Rearick, & Weiss, 2001). Many remarked that their knowledge of student learning had been validated and they felt empowered in their new role as reflective and inquiring educators (Crow, Adams, Bachman, Peterson, Vickery, & Barnhardt, 1998). This empowerment often provided them with immense professional growth and an enhanced sense of accomplishment and self-efficacy as their efforts to become involved in educational decision making were realized. These elements are all underlying dimensions within the framework of teacher empowerment proposed by Short (1994). Furthermore, through a heightened sense of self-awareness and critical reflection, feelings of empowerment can ultimately contribute to an enhanced role for teachers in efforts of school improvement and student achievement (Fry, Fugerer, Harvey, McKay, & Robinson, 1999; Sagor, 2000; Warrican, 2006).

Guides to Action Research

Current Teacher Action Research Opportunities

Tuesday, June 12, 2007

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)